Talking about Education

The social media environment has changed in the past 5 years. Blogging used to be more of a thing, but now podcasts and Twitter threads and so on have often served as more effective (or convenient) way to share ideas with a broader audience.

I have had the pleasure to join several podcasts over the past year on a variety of topics. I am sharing them here in reverse chronological order.

Rebuilding after 2020-21 with the Human Restoration Project

Episode description: “In our conversation, Dr. Horn and I discuss how teachers can wrap up the 2020-2021 school year through reflection. How can we build a better system after seeing the inequities, problems, and challenges that this school year has highlighted? And, how do we build a classroom in spite of a system that often demotivates and disenfranchises educators?”

Is It Time to Cancel Teach Like a Champion? on Have You Heard podcast

Episode description: “Teach Like a Champion, the best-selling guide to effective teaching by Doug Lemov, has sold millions of copies. But is it racist? Have You Heard hears from teachers and researchers who argue that Lemov’s approach embodies “carceral” pedagogy. And because we have a thing about education history, we trace the concept all the way back to 1895. Special guests: Ilana Horn, Joe Truss and Layla Treuhaft-Ali.“

How to Get Your Students Motivated on Making Math Moments that Matter podcast

Episode description: “In this episode we speak with Ilana Horn – A professor of math education at Vanderbilt University. Ilana’s work is motivated by the underperformance of students in mathematics. Today we talk with Ilana about her book Motivated and what is needed to START to motivate your students.

“Ilana calls her book the prequel to Peg Smith and Mary K. Stein’s book The 5 Practices to Orchestrating Productive Mathematical Discussions, and we can’t agree more. There’s so much that we overlook when planning lessons that will either make or break what you do in the classroom.”

2020 Research from the Teacher Learning Lab at Vanderbilt

It’s that time of year — I get to brag on my amazing students and mentees for their important research.

(I am going to focus on journal articles here, but if you want to see more about what we are finding on the National Science Foundation-sponsored project, my lab’s major current research project, Supporting Instructional Growth in Mathematics study (Project SIGMa), you can look here.)

For those of you not familiar with my lab, we study teachers’ sensemaking from an anthropological perspective. We blend a mix of methods to really dig into how teachers (mostly math teachers, mostly teaching in urban secondary schools) understand what they are up to, with an eye towards how different social arrangements and activities shape those meanings. This approach supports the development of ecologically valid models of teachers’ learning and, relatedly, context-sensitive designs for instructional improvement.

Looking at how teachers monitor student-led work

Nadav Ehrenfeld & Ilana Horn (2020). Initiation-entry-focus-exit and participation: a framework for understanding teacher groupwork monitoring routines. Educational Studies in Mathematics. 103, 251–272 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-020-09939-2

In this paper, we offer a framework for teacher monitoring routines—a consequential yet understudied aspect of instruction when teachers oversee students’ working together. Using a comparative case study design, we examine eight lessons of experienced secondary mathematics teachers, identifying common interactional routines that they take up with variation. We present a framework that illuminates the common moves teachers make while monitoring, including how they initiate conversations with students, their forms of conversational entry, the focus of their interactions, when and how they exit the interaction as well as the conversation’s overall participation pattern. We illustrate the framework through our focal cases, highlighting the instructional issues the different enactments engage. By breaking down the complex work of groupwork monitoring, this study informs both researchers and teachers in understanding the teachers’ role in supporting students’ collaborative mathematical sensemaking.

(Here is a blog post written by folks at Vosaic, the video-coding software that we used in this analysis.)

Considering Ethical Dimensions of Mathematics Teaching

Grace A. Chen, Samantha Marshall, & Ilana Seidel Horn (2020). “How do I choose?” Mathematics Teachers’ Sensemaking about Pedagogical Responsibility. Pedagogy, Culture & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2020.1735497

Teachers’ decisions are often undergirded by their sense of pedagogical responsibility: whom and what they feel beholden to. However, research on teacher sensemaking has rarely examined how teachers reason about their pedagogical responsibilities. The study analyzed an emotional conversation among urban mathematics teachers about what they teach mathematics for, given the many non-mathematical challenges they and their students face. The familiarity and simplicity of love and life skills narratives deployed to describe what it means to be a good teacher and to do good teaching may be comforting, but limit teachers’ engagement with other authentic forms of pedagogical reasoning about their pedagogical responsibility in complex sociopolitical contexts. The findings reveal the importance of opportunities to explore alternate possibilities ‘for what,’ especially within structured and supportive teacher collaborative group

(Here is a research outreach document that summarizes this work nicely.)

Taking Seriously the Meaningful Preparation of Black Women Teachers

Mariah D. Harmon and Ilana Seidel Horn (in press). Seeking Healing through Black Sisterhood: Examining the Affordances of a Counterspace for Black Women Pre-Service Teachers. AILACTE Journal.

Calls to increase diversity in the United States teacher workforce emphasize benefits to students without strategic consideration of minoritized teachers’ needs. In this ethnographic study, we investigate the affordances of a counterspace for Black women pre-service teachers in a predominantly white institution to support their development as educators. Using a grounded theory approach, we analyze fieldnotes from one meeting to understand how the counterspace offered participants a space to reconcile with contradictions experienced working in schools. The counterspace contributed to participants’ healing in three ways: (1) it made space for participants to interrogate their own experiences in U.S. schools; (2) it offered insider connections, a fundamental sense of belonging and legitimacy; and (3) it busted the myth of the monolith, by inviting the breadth of Black women’s stories and histories. These findings suggest that building community through shared identity markers can foster a rich environment for teacher development.

The Impact of Strong Teacher Collaboration on Teachers’ Advice-Seeking Networks

Ilana Horn, Brette Garner, I-Chien Chen, and Kenneth A. Frank. (2020, April). “Seeing Colleagues as Learning Resources: The Influence of Mathematics Teacher Meetings on Advice-Seeking Social Networks.” AERA Open 6(2): 2332858420914898.

Teacher collaboration is often assumed to support school’s ongoing improvement, but it is unclear how formal learning opportunities in teacher workgroups shape informal ones. In this mixed methods study, we examined 77 teacher collaborative meetings from 24 schools representing 116 teacher pairs. We coupled qualitative analysis of the learning opportunities in formal meetings with quantitative analysis of teachers’ advice-seeking ties in informal social networks. We found that teachers’ coparticipation in learning-rich, high-depth meetings strongly predicted the formation of new advice-seeking ties. What is more, these new informal ties were linked to growth in teachers’ expertise, pointing to added value of teachers’ participation in high-depth teacher collaboration.

Methods for Studying Teachers’ Collaborative Learning

Ilana Horn & Nicole A. Bannister (2020, February). Interactionist Perspectives on Mathematics Teachers’ Collaborative Learning. International Commission of Mathematics Instruction Study Conference. Lisbon, Portugal. (Link to paper)

Interactionist analyses of teachers’ professional conversations respond to open questions about collaborative mathematics teacher learning in ways that are proximal and relevant to their lived experiences and everyday work. Drawing on situative theories of learning, we analyze partitioned conversational records for evidence of learning. Key findings from our prior studies point to four design considerations for interventions that seek to leverage the potential of mathematics teacher collaboration: (1) deeper collaboration is relatively novel and rare for teachers; (2) development of a shared vision for teaching is essential and deliberate work; (3) adequate representations of teaching are necessary for supporting intersubjectivity about core instructional ideas; and (4) frames are an important site for reconceptualization of key ideas about teaching. Examples from our current projects show the application and broader utility of these findings for interventions that use collaboration to support mathematics teacher learning.

A STRANGE NEW WORLD: PRE-PRINTS

For the first time, I have also been experimenting with pre-prints. Grace Chen and I received support from the Gates Mindset Scholars network, where we were introduced to this practice. Then, last spring, Katherine Schneeberger McGugan and I embarked on an interview study of experienced secondary mathematics teachers’ transitions to virtual instruction during the pandemic. Because of the timeliness of our findings, we felt compelled to share on a quicker timeline than the usual publication process permits. Finally, Grace and I collaborated with sociologist Jessica Calarco on an analysis of inequalities produced through elementary and middle school math homework, which also seemed urgent, since currently all school is homework.

A Literature Review Synthesizing on How Students Get Marginalized in Mathematics Classrooms

Grace A. Chen & Ilana Seidel Horn (2020, August). Mechanisms of Marginalization in Mathematics Classrooms: A Call to Critical Bifocality. DOI: 10.31219/osf.io/nv6kd

In light of decades of research seeking to document and transform extensive injustices in mathematics education in the United States, we examine how different conceptualizations of which students are marginalized and by what processes they are marginalized in order to contribute to a more thorough, nuanced understanding of marginalization in mathematics education. To do so, we review literature theorizing marginalization across social identity categories and synthesize the disciplinary traditions they draw on and the mechanisms of marginalization they articulate. Findings from this review highlight the normality of marginalization in mathematics education, the material and ideological means of marginalization, and the interlacing of individual and structural sources of marginalization. As a result, we argue for critical bifocality in attending simultaneously to the processes of marginalization that occur in individual mathematics classrooms alongside the systemic structures that organize marginalization in society more broadly.

How Experienced Secondary Urban Mathematics Teachers Transitioned to Virtual Teaching

Ilana Seidel Horn & Katherine Schneeberger McGugan (2020, June). Adaptive expertise in mathematics teaching during a crisis: How highly-committed secondary U.S. mathematics teachers adjusted their instruction in the COVID-19 pandemic. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.13720.83200

The global COVID-19 pandemic disrupted education across the world, requiring a quick re-organization of instruction on a large scale. In this study, we examine how highly-committed secondary mathematics teachers in the U.S. responded as they shifted their instruction online. Building off a four-year research practice partnership, we interviewed 11 secondary mathematics teachers whom we conceptualize as adaptive experts –– experienced teachers who responded flexibly and with an openness to learning –– about their pivot to online instruction. Conducting semi-structured interviews during school closures, we found that, while the teachers maintained commitments to ambitious and equitable teaching, new dilemmas arose around time management, centering student thinking, and building and maintaining relationships. By documenting how highly-reflective educators responded to this crisis, we highlight issues for others to anticipate in times of educational disruption, as well as contribute to the field’s understanding of adaptive expertise in mathematics teaching.

Jessica Calarco, Ilana Horn, and Grace A. Chen (2020, August). “You Need to Be More Responsible”: How Math Homework Operates as a Status-Reinforcing Process in School. DOI: 10.31235/osf.io/xf96q

Practices like ability grouping, tracking, and standardized testing operate as status-reinforcing processes—amplifying then naturalizing unequal student outcomes. Using a longitudinal, ethnographic study following students from elementary to middle school, we examine whether math homework can operate similarly. Because of inequalities in families’ resources for supporting homework, higher-SES students’ homework was more consistently complete and correct than lower-SES students’ homework. Teachers acknowledged these unequal homework production contexts. Yet, official policies treated homework as an individual endeavor, leading teachers to interpret and respond to homework in status-reinforcing ways. Students with consistently correct and complete homework were seen as responsible, capable, and motivated and rewarded with praise and opportunities. Other students were seen as irresponsible, incapable, and unmotivated; they were punished and docked points. These practices were status-enhancing for higher-SES students and status-degrading for lower-SES students. We discuss implications for homework policies, parent involvement, and interpretations of inequalities in school.

Finally, I would be remiss if I did not shout out a new book by my former advisee, Elizabeth Self, and my colleague, Barb Stengel: Toward Anti-Oppressive Teaching: Designing and Using Simulated Encounters. They wrote about the incredible work they have led on the SHIFT Project, which has transformed Peabody’s teacher preparation program.

We will have more to share in the new year… Patricia Buenrostro and Nadav Ehrenfeld have a paper about a teacher’s reasoning about productive struggle, a key construct in a lot of mathematics reform … Samantha Marshall’s recently defended dissertation, Responsive, Locally-Relevant Coaching: Supporting STEM Teachers’ Learning of Justice-Oriented Pedagogies, should be yielding some publications … and our team, led by myself and Brette Garner, is developing a book describing our theory of teacher learning.

#EndCarceralPedagogy #ScholarStrike

About 5 years ago, I wrote a blog post calling out the problematics of Teach Like a Champion (TLAC). It gained a bit of traction, started some conversations about why this very controlling pedagogy was becoming so popular in schools that served primarily Black and brown children.

After this past summer of 2020, with the murders of George Floyd, Breana Taylor, Amaud Arbery and so many others, the Black Lives Matter movement became re-centered on the conversation about anti-Black racism in the U.S. and its all too frequent lethal consequences.

In June, I participated in #Strike4BlackLives, led by physicist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, re-upping that post along with a more explicit call to name the dominating and controlling TLAC approach as a tool for anti-Blackness. I encouraged people who agreed with my perspective to let their opinions be known on public forums like Amazon or Goodreads, since the book’s popularity continues unabated.

Subsequently, education journalist Jennifer Berkshire and historian Jack Schneider did a story on their Have You Heard podcast about TLAC and its racism problem. Interestingly, I learned from listening to the episode that TLAC’s emphasis on controlling Black children’s bodies has eerie resonances with Reconstruction-era teaching approaches for formerly enslaved children, with a lot of anti-Black notions of “correcting” their amoral character.

So here we are in September. I am participating on Tuesday, September 8 in the Scholar Strike for Racial Justice, a mass action of higher education professionals protesting racist policing, state violence against communities of color, mass incarceration and other manifestations of racism.

I encourage you to follow #SCHOLARSTRIKE on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and to engage with the teach-in occurring on the Scholar Strike YouTube channel.

My contribution to the teach-in is available here. I will also be holding a Twitter #SlowChat using the #EndCarceralPedagogy hashtag on Tuesday, September 8, posting questions every hour from 8 AM to 4 PM Central time. Please join me if you are able to .

What could be? On education and hope

Maxine Greene, a renowned philosopher at Columbia Teachers College, loved to teach. At 93 years old, she still held seminars in her apartment. During one of these sessions, she asked her students, “What is the purpose of education?”

She listened as they debated and discussed. Then, drawing on the wisdom of her decades of attention to such important questions, she shared, saying that, in her view, education’s purpose is to help students to meaningfully put together three words: What could be?

I heard this story yesterday from one of the students who had attended that class. It reminded me of a fundamental truth: Education, at its best, is a profession of hope. Education should equip students with the tools they need to recreate our world and make it better. Although our society does not adequately acknowledge their importance, educators have the vital charge to guide the next generation.

This core belief drives my work. I believe children matter. I believe they deserve a chance to find out who they are and how they can fit into the world while making it a better place. I believe that the best teaching takes intelligence, knowledge, creativity, and careful attention to who children are, and I believe that all children deserve to experience that.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s, I was fortunate to have a handful of teachers who brought this sense of idealistic purpose to their work, and it made all the difference in my life. I became a teacher in the early 1990s, during an era of progressive optimism. I learned from my mentors how to develop classrooms that made space for children –– their ideas, their strengths, their struggles, their cultures, their stories, and their dreams. I learned to always be curious about that work, since it is always in progress.

As a result, this past decade has been hard on me. It seems that, in the U.S., we have moved further away from this idealistic vision of education. To name a handful of examples, the 2010s saw the proliferation of toxic accountability policies that treated “good teaching” as entirely measurable by shoddy testing instruments, the devaluation of professional preparation of teachers (and of the profession in general), the normalization of under-resourced classrooms (alongside the trope of “heartwarming” community generosity to fill the gaps that should never be there in the first place), record numbers of school shootings that do not even make headlines, the rise of bigoted speech and hateful acts, and the reduction of the relational work of teaching to carceral pedagogies preoccupied with the control children’s bodies over the development of their intellect and agency. In other words, it has been a demoralizing decade.

How have we arrived here? I am sure there are more answers to that question than I can muster in a blogpost, but I can share one thing that has struck me about how we got where we are today. Many folks seem to fail to grasp the systems we are developing. Too often, people treat problems in education as a matter of tweaking one component or another. In contrast to thinking about individual parts, systems thinking requires a holistic view of how components interrelate, the way that different contextual details shift those relationships, and demands alertness to any unintended consequences to educational designs.

In my view, many of the shortcomings of the past two decades come from our failure to take in the systems (such as they are) that we are creating and living in.

As one example, a good education system should not require as much strategy and savvy as ours currently does. The public’s commitment to a quality education for all, while it may have never been strong, was at least given lip service by politicians and others professing to have an investment in democracy. Now, notions of education as a public good have been replaced with individualistic notions of education as a personal choice. However, if we see our society as a system –– if we believe that we are interdependent and not just individual components –– we would feel the urgency around the need to prioritize the former set of ideas over the latter.

Education should not simply be viewed as the sum total of people’s “personal choices.” The language of “choice” may appeal to notions of liberty, but it increases the parental burden of somehow prognosticating, through “school choice fairs” and one-hour walk-throughs, how a particular child will be supported in a setting they only have partial access to.

Even more damaging, the rhetoric of choice is false. Just like gerrymandering rigs the political game, redistricting efforts across the U.S. rigs the educational game. White, affluent families are seceding from districts, hoarding resources for their children and leaving those with fewer resources even more strapped. These trends strongly signal the abandonment of our commitment to education as a public good. Meanwhile, the more students are burdened with the narrative that the quality of their education is entirely on them, the less responsibility we have as a society to ensure that the opportunities are actually there.

In sum, my view on the current U.S. educational landscape is fairly grim. At the same time, in the spirit of Maxine Greene’s essential question, I want to focus this next decade on what could be.

So what could be, if we should, as a society, decide to work for it? We could re-invest in schools –– all schools, in all neighborhoods, serving all students–– so they do not have to depend on a random windfall of a generous philanthropist to meet their basic needs. We could invest in teachers so that they have the time, materials, training, salaries, and professional support they need to do their work well. We could reduce test-based accountability and instead invest in students’ authentic learning. Generally speaking, we could invest in students’ broader humanity, with fully funded arts, music, and job training programs, alongside high quality academics. We could acknowledge our interdependence as a society and return to a commitment to education as a public good.

What could be?

Education could truly embrace its potential as the profession of hope. That would be a great project for the new decade.

Let Them Laugh: Using Humor in Math Class

Humor serves many functions in my life. Noticing the absurd. Playing with unexpected associations and enjoying the surprise. Sharing inside jokes with friends. Resisting, venting, and gaining temporary relief about abuses of power by belittling them with laughter.

I am obviously not unique in this. Humor is a crucial part of being human in a complex (and often ridiculous) world.

But humor –– especially in certain forms –– is not always welcome in school. What does this mean for students’ expressions of their humanity? Think about the well known class clown archetype. Some educators use this label with derision, assuming students step into this role for negative reasons, like avoiding work or garnering attention that distracts from lessons, making the teacher’s job harder.

The essential role of humor for many people’s ways of being in the world is thus in tension with many ways of “doing school” that require deference to the teacher’s authority. This leads to dilemmas for those of us who want to build inclusive and humanizing classrooms. We get many messages from administrators, teacher educators, and other colleagues that a good class is an orderly class, one where the teacher leads and students follow, not one where spontaneous outbursts might be embraced and incorporated, where laughter might be happening in small groups, or where a class clown can have a legitimate place in learning –– even be an important member of the community.

Personally, I knew early on I was going to struggle to navigate my own predilections with these common images of “good teaching.” During my student teaching, I accompanied a group of seventh graders on a field trip to the courthouse to observe a trial. Our guide welcomed us to the courthouse and looked at the docket to see what case we would be viewing.

“Oh, good. It’s a nice, clean trial,” she said.

“Dang!” said one student, leading me to snicker audibly.

Some nearby students turned to me in surprise: Wasn’t I supposed to scold him for his lack of decorum? Perhaps I was. But as a human, I loved his reaction for its honesty. In fact, much of my joy as an educator comes from engaging students’ clear eyed honesty, which extends to their disappointment about a “nice, clean trial.” I realized then that I would need to develop a way to enforce behavioral norms (many of which I myself find challenging to adhere to) and my genuine appreciation for his rascally reaction.

Let me be clear. I am not suggesting an “anything goes” approach to humor in schools. Educators resist humor for many reasons. Humor can be subversive. Humor can be exclusionary. And, obviously, humor can be mean. But shouldn’t we have a way of inviting some humor into our math classrooms? Can we pick and choose with a little more care?

Seeking a framework for humor in math classrooms

Recently, I have been working with my colleague, Dr. Nicole Joseph, and an undergraduate research assistant, Yasmin Aguillon, to look at humor in math classrooms.

Dr. J and I are working on this together for a few reasons. We share a commitment to welcoming students’ full humanity into the math classroom and seek to help teachers understand what that entails. In one of her recent articles, she and her colleagues heard from Black girls that they wanted math classes to be a place to be their full selves, including the silly and “goofy” (an adjective one of the participants used). We also share that our ways of being in the world do not require us to put our own silliness in a box when we are doing work. We can sing, tell jokes, code switch –– play –– while we are working on things we deeply care about. This, in our lived experience, is not at odds with deep and rigorous work. In fact, bringing our authentic selves to our work only enhances its depth and rigor.

Dr. Nicole Joseph and me, clowning with math at the Escher Museum

To build our framework, we draw on several sources. First, we have looked at research on humor in social life, especially classrooms. Second, we have looked at classroom level data from my recent research project where students are clowning around. Finally, we conducted a completely unscientific #MTBoS #iteachmath twitter poll on whether math teachers felt humor had a place in the classroom.

We are working on a fuller discussion of humor in math class, but for the purposes of this blog post, I want to suggest the following:

The playful –– and even the subversive –– aspects of humor belong in math class, not only because they allow students to more fully be themselves, but because they embody important mathematical habits of mind and allow entrée for students’ broader identities. At the same time, we recognize that inviting humor may require teachers to develop new forms of teaching and cultural competence.

Playful and subversive humor belongs in math class

If you think about the pleasurable aha! of mathematics, you might notice its similarity to the pleasurable moment of getting a joke. The common experience is that of insight.

Mathematics has its share of jokers. Aside from famous people like Lewis Carroll who enjoyed playing with logic, we have mathematical entities that upend the order of things. Infinity and zero subversively violate our expectations of how operations and functions work: what do you mean we can’t divide by zero? why do functions change when we imagine taking them to infinity? The whole field of topology essentially invites us to imagine that objects as made of rubber, making a coffee mug “the same” as a donut. These delights of insight and absurdity tickle any good rascal.

When we invite humor into math class, we also change the emotional tenor of what we are doing. Humor positively effects learning by releasing tension. When we laugh, we are at often more at ease. Humor has even been shown to improve students’ performance on tests. Maybe laughing sessions can improve study sessions. Humor can build rapport, either with individual students or with a classroom community. I know a teacher who strategically looks for something to laugh at with each of his classes, so that they can have a shared inside joke.

Humor also invites students’ broader identities into their learning. Who we are is fundamental to how we make sense of the world; when we have to leave part of our selves at the door in order to be seen as “acceptable,” we abandon crucial sensemaking resources. Although laughing at my student’s response to the “nice, clean” court case may have not followed a proper teacher script, it appreciated him for the twelve year old boy that he was and his understandable wish for a meatier, dirtier case. In sanitizing the world for children, often in the name of protection, we omit important details. By the time they are twelve, they have often started to question who is actually protected through adult judgments of “appropriateness.” This kind of questioning signals curiosity and intelligence.

Why wouldn’t we welcome such attitudes in school?

Teachers may need new forms of teaching competence to productively support humor in class

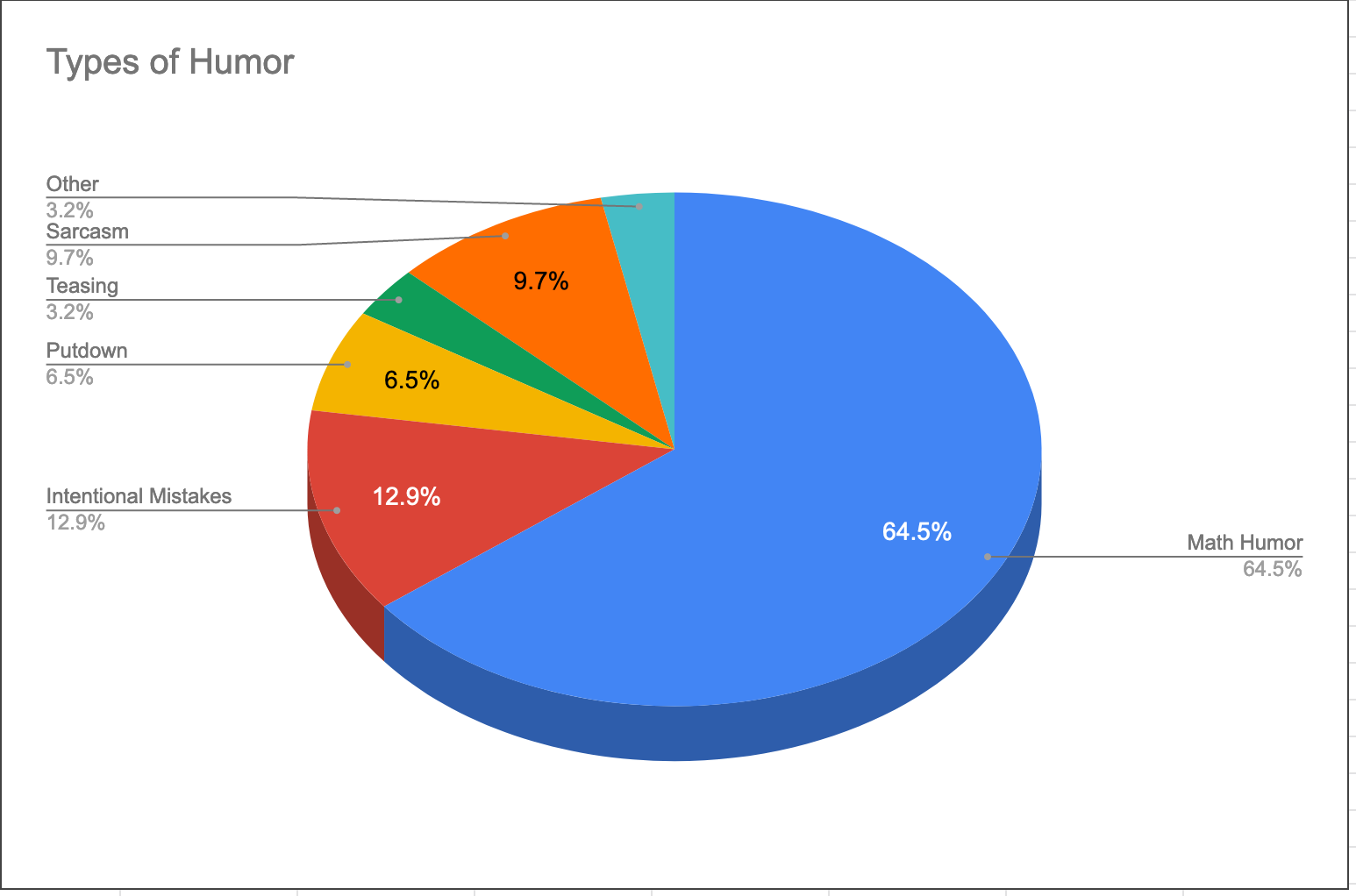

Indeed, in our completely unscientific twitter poll of 741 people on the Internet, 94% of respondents agreed with our idea that humor belongs in math class. Among the 31 respondents who elaborated on their reasoning, we found that most people (64.5%) referred to math humor, like math puns and math jokes. The next most mentioned form of humor were intentional mistakes (12.9%), a pedagogical strategy where teachers present an incorrect solution and humorously play at not understanding to prompt student explanations. Most of the remaining responses referred to negative forms of humor such as sarcasm (9.7%), put downs (6.5%), or teasing (3.2%).

What is interesting about these responses, as limited as they might be because of the nature of the poll, is that the positive examples of humor are teacher-centered; that is, they are controlled by the teachers’ choices about curriculum and pedagogy. The negative examples signal adverse relationships, whether from students to the teacher, teacher to students, or among students themselves. But, in the examples offered, we do not see examples of how students themselves can be a positive source of classroom humor.

We suspect this is because student-derived humor is trickier teaching terrain. (Or it may be due to the limitations of our completely unscientific Twitter poll.)

Building off of the first interpretation, we acknowledge that there are many shades of gray when we laugh with students. How do we navigate the ideas of “appropriate” that can vary so much within a classroom, let alone a broader school community?

Once we open the door to students’ humor, how do we ensure that positive humor does not cross over into the exclusionary humor that can lead to hurt feelings and negative social dynamics?

How do we feel if students are laughing at us? Or even if we are not the target, how do we feel if they are sharing a joke that, for reasons of generational, linguistic, or cultural differences, we don’t get? What would it mean for us, as teachers, if we are on the outside of the humor?

We suspect that productively managing humor requires a unique form of teaching competence. As the outsider example suggests, this also includes forms of cultural competence.

We are just starting to figure out how to name and describe what these teaching competencies might look like, using the classroom data examples. From our initial look, we think humor competence for teaching involves a form of self-knowledge –– knowing yourself, being comfortable with your own identities, having the humility to laugh at yourself. But it also involves relational skills of reading students’ reactions, developing rapport to invite open communication, and having strategies for repairing relationships when lines get crossed or feelings hurt.

We would love to hear more about how you use humor in math class to make it a more humanizing space. Math class could use a few more laughs.

This post was written as a part of The Virtual Conference on Humanizing Mathematics (#VConHM on Twitter)

Modeling Mathematical Aesthetics

Note: This post was written by my two doctoral students, Lara Jasien and Nadav Ehrenfeld, as part of the Virtual Conference on Mathematical Flavors. This essay responds to the prompt “How do teachers move the needle on what their kids think about the doing of math?” It is also part of a strand inside that conference, inspired by an essay by Tim Gowers,“Two Cultures in Mathematics.“

Note: This post was written by my two doctoral students, Lara Jasien and Nadav Ehrenfeld, as part of the Virtual Conference on Mathematical Flavors. This essay responds to the prompt “How do teachers move the needle on what their kids think about the doing of math?” It is also part of a strand inside that conference, inspired by an essay by Tim Gowers,“Two Cultures in Mathematics.“

Before we begin responding to Gowers’ essay, we’d like to share a little bit about what draws us to this conversation. As budding researchers of mathematics teaching and learning, we spend our days watching teachers go about their daily routines with their students. We look for the ways teachers support their students to engage in meaningful learning and position them as capable, curious thinkers. Our work is fundamentally concerned with the ways classroom culture shapes what it means to teach, learn, and do mathematics. Gowers’ essay provides us with an interesting new lens on the role of culture in mathematics. We want to share (what we think is) a problem-of-practice worth considering and then point to an often overlooked teaching move that we recently saw a teacher use in ways that counteracted this problem-of-practice.

As educators and learners of mathematics, our experiences usually involve engaging students in correctly solving mathematical problems that are predetermined, handed down to us over generations through textbooks and pacing guides (with slight variations). This means that students have few opportunities to engage in a core element of mathematics — finding and articulating problems that are interesting to solve. We think this is intimately connected to a missing aspect of mathematics culture in typical math education: the mathematical aesthetic. Mathematicians’ aesthetic tastes and values lead them to pursue some problems, solution strategies, and forms of proof write-ups over others. When mathematicians’ inquiry is driven by their aesthetics, they engage in exploration, noticing, wondering, and problem-posing.

The mathematical aesthetic is the mechanism by which mathematicians distinguish between what they experience as meaningful, interesting mathematics and trivial, boring mathematics. In his essay, The Two Cultures of Mathematics, W.T. Gowers identified two groups of mathematicians who find each other’s work equally distasteful (with a little dramatic flare): problem solving mathematicians and theoretical mathematicians. Typically, school instruction exposes students to problems that fit both cultures of mathematics: Some school mathematics is done for mathematics sake, some is done for the purpose of real life or pseudo real life (word problems) problem solving. Yet, when do students have the opportunity to develop aesthetic preferences for different ways of engaging with and thinking about mathematics?

In our work, we have seen classrooms with cultures that support students in posing questions to their peers — questions like, I wonder if there is a reason for that? or What’s your hunch?. In these classrooms, we see students begin to be interested in and passionate about mathematics. In our minds, when students develop such passionate tastes about meaningful mathematics, we are on a good track for empowering our students for success.

The questions we just mentioned are actually questions we recently overheard a teacher asking her students as her last statement before exiting small group conversations. We consider her enthusiastic questions to be a form of modelling mathematical aesthetics, prompting students to be curious, explore, wonder, and use their intuition. While ideally the classroom culture would eventually lead to students asking themselves and each other these kinds of aesthetic questions, we know that our own authentic intellectual curiosity as educators does not go unnoticed by our students. Importantly, this teacher did not ask these questions and then hang around and wait for student answers. She left the students with juicy questions that they could investigate together.

As teachers, we rarely get feedback on how our exit moves from small group conversations affect their conversation or the classroom culture. Of course, some exit strategies –– such as telling students the answer or funneling them towards it –– will clearly lead to cultures where students see mathematics as a discipline of quick-and-correct answer finding. This view of mathematics can preclude opportunities for students to develop as autonomous doers and thinkers of mathematics. Fortunately, options for productive exit strategies and modelling of intellectual interests are many. These options also present new decision-making challenges to teachers as what happens when we exit the conversation becomes far less predictable. Our students do not need to have the same mathematical tastes as we do, but we do want them to feel empowered and intellectually curious in our classrooms. By foregrounding noticing, wondering, and problem-posing as authentic mathematical practices, we can support students in developing their own mathematical aesthetic. Of course, doing so requires us to model genuine intellectual curiosity, make room for uncertainty and ambiguity in our tasks (groupworthy!), create access to multiple resources for pursuing mathematical questions (Google is acceptable!), and scaffold for conversation rather than bottom-lines (exit moves!). Leaving students with a juicy, natural question is a start.

You Are More than Your Achievements

Last night, I was invited to address the new members of the National Honors Society at my daughter Naomi’s high school. I am sharing the text of my speech here.

Good evening. First, let me congratulate you on all the hard work and talent that is reflected by your being here tonight. Your presence in this auditorium means that have worked hard. You have earned good grades. You have demonstrated a commitment to your community.

No doubt, you deserve to be congratulated –– to be honored –– for all of these things.

I too am honored to be here this evening, to share in your accomplishment, to beam alongside your parents.

As Naomi mentioned, in addition to being a parent here, I am a professor. My research is in the field of math education — secondary math education, in fact. So I have spent a lot of the last 25 years in public schools, especially urban high schools. In that capacity, get to work with and talk to kids and teachers about their experiences.

I do my research anthropologically: that is, I study schools as cultural systems and try to understand what makes them work, what values they convey through their customs and rituals, with an eye toward helping them become places that serve our country’s democratic ideals. When U.S. public education was founded in the 1800s, one of its central purposes was to build citizens who can make good lives for themselves and contribute to our society.

After 25 years of working and living in schools all across the U.S. (and even a few of them abroad), I can say: schools are wonderful and terrible.

Sometimes even one school is both at the same time.

At their best, schools serve the democratic ideals I just described. The open up opportunities, promote social mobility, and develop informed and thoughtful citizens.

When schools operate in this way, they fill me with hope and optimism. I see young people discovering what is possible, preparing themselves as the next generation of leaders.

At their worst, schools work against democratic ideals. They operate in ways that preserve opportunities for some while shutting others out. They contribute to social reproduction. They fall short of their mission to develop informed and thoughtful citizens.

When schools operate in that way, I imagine them as heartless machines, pumping kids through, sorting them on a conveyor belt toward paths of success or failure.

My observations about the dual possibilities of schooling are not meant to denigrate your important accomplishment tonight. Your induction into NHS means that you have been sorted into the academic successes.

To the contrary, my observation only increases my accolades and admiration, because it means that, in addition to having talent and working hard, many of you have very likely managed to advocate for yourselves, size up a system that is not always kind, and maintain a strong academic record in spite of various blows to your humanity along the way.

Every one of you has a story. Every one of you can tell me about how you got here tonight. And if your stories are like the stories of other high achieving students I have met over the years, along with your talent and hard work, your presence here tonight very likely also shows resilience and savvy. This deserves its own congratulations and it will also no doubt serve you well in your future.

Becoming a member of NHS marks you as an achiever. The culture of achievement to which you are being formally inducted here is a wonderful thing. It gives your families cause for pride and celebration. It will open doors to jobs and colleges for you.

Spending time in schools and studying adolescents in education, I know that (perhaps for some of you more than others), there are also personal costs for joining the culture of achievement. I want to take a moment to consider those, out of a sense of care and concern for you and your long term wellbeing.

May is Mental Health Awareness month, and we know right now that young people are facing greater rates of anxiety and depression than they have previously. The last statistic I saw reported about 1 out of 5 college students experiencing these things. That’s about a 33% increase over previous rates.

People my age like to think this is, in part, because of social media — you put your social lives online. On Snapchat and Instagram, you are constantly comparing yourselves to others. We even have a word –– FoMO –– to describe the special angst of missing out on things you see others doing that, in my generation, we most likely would have never known were happening.

I think there is more going on than that. I think there are vulnerabilities here in this room that are not often enough addressed.

I am bringing up mental health because it matters for your long term happiness. I teach in a university. I see students, just like you, who have successfully navigated the perils of schooling, who got sorted in the right ways. They, like you, are creative, inquisitive, driven. Sometimes, they end up in my office, and I offer tissues as they share their concerns and their worries. I see that too often they are led to believe that their value as a person is directly tied to their achievement.

So much emphasis in high school is on getting into the best college. And what happens if you manage to get there? We all hear of the benefits: Great education, valuable social network, important internship opportunities, a “brand name” university on your resume.

What we hear about a lot less are the risks to you, as a person and a human being.

Jamie O’Keeffe, an educational researcher at Stanford University, studied high achieving undergraduates at a top-tier university and how they contend with the pressures to achieve. She describes that when students “make it” to a selective university, they feel pressure to maintain the image of a “total winner”: the ideal self-made individual who excels without effort, confidently demonstrating genuine intellectual passion and desire to make a difference in the world, while effectively realizing increasingly greater achievements.

Paradoxically, this pressure makes it harder to maintain a sense of wellbeing. They experience stress, insecurity, and self-criticism, as any sense of struggle or failure feels like it is evidence against their legitimacy there. We have a name for that feeling. It’s called impostor syndrome. These feelings are amplified for first generation college students or students from historically marginalized groups.

So what is my message? Do I recommend slacking off? Bailing on NHS and aiming for the middle?

No. Absolutely not. As I started out saying, what you have done is commendable, maybe more so than many even realize. It is worthy of the honor you are receiving.

All of you sitting here belong here.

I suggest you follow Albert Einstein’s advice: “Try not to become a person of success, but rather try to become a person of value.”

I just want you to remember that you are more than your achievements. You are more than what you can list on the Common App next Fall. In fact, much of what is so precious about you won’t ever make it into that form.

I also am asking you to remember this. Aim to be honorable, not only in the ways that got you here tonight, but honorable to your friend who needs you to listen. Be honorable as children to your parents who have cared for you all these years. Be honorable as members of your communities –– your churches, synagogues, mosques, or whatever you consider your community. Be honorable to strangers in need. Be honorable to the students who struggle more than you do, the ones who are not here today.

Being honorable means doing what is right. And doing what is right is not always easy. It is not always obvious. Part of being honorable involves really knowing what you stand for and what you care about. It means knowing who you are. That should, ideally, be a part of your education too.

What does this have to do with mental health? In my experience, people who know who they are tend to hit those challenges, those setbacks, those inevitable and often unexpected bumps in the road with, if not grace, with inner strength. They get knocked down, but they see a bigger picture, a larger purpose. They have people they can lean on, a sense of their own value beyond whatever went wrong. In this way, they maintain their perspective, even when they are shown to be less than a “total winner.”

From honor –– true honor –– comes strength in the face of adversity.

So congratulations on this honor. Be sure to cultivate it, and I wish you all a good life.

Great Stuff from My Team in 2017

One of the great things about coming up in this profession is seeing all the great work my students (current and former) produce. As you may note, their work varies yet addresses some central themes. I hope you will read any papers that sound interesting.

Without further ado, here are some of the highlights from 2017:

Purpose

Though test-based accountability policies seek to redress educational inequities, their underlying theories of action treat inequality as a technical problem rather than a political one: data point educators toward ameliorative actions without forcing them to confront systemic inequities that contribute to achievement disparities. To highlight the problematic nature of this tension, the purpose of this paper is to identify key problems with the techno-rational logic of accountability policies and reflect on the ways in which they influence teachers’ data-use practices.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper illustrates the data use practices of a workgroup of sixth-grade math educators. Their meeting represents a “best case” of commonplace practice: during a full-day professional development session, they used data from a standardized district benchmark assessment with support from an expert instructional leader. This sociolinguistic analysis examines episodes of data reasoning to understand the links between the educators’ interpretations and instructional decisions.

Findings

This paper identifies three primary issues with test-based accountability policies: reducing complex constructs to quantitative variables, valuing remediation over instructional improvement, and enacting faith in instrument validity. At the same time, possibilities for equitable instruction were foreclosed, as teachers analyzed data in ways that gave little consideration of students’ cultural identities or funds of knowledge.

Social implications

Test-based accountability policies do not compel educators to use data to address the deeper issues of equity, thereby inadvertently reinforcing biased systems and positioning students from marginalized backgrounds at an educational disadvantage.

For the Love of Children

Outside of Tehama Elementary School after yesterday’s shooting. Photo credit: Jim Schultz. Source: USA Today

Our society does not love its children.

It has been almost 5 years since the Sandy Hook shootings, where twenty children, aged 6 and 7, and six adults were killed in cold blood. In these intervening years, not only have we failed to pass common sense gun laws, we seem to have grown numb to the violence. Yesterday’s shooting at Tehama Elementary School did not even make the landing page of the New York Times online this morning.

Our society does not love its children.

Violence against children is normalized. I do not see collective will to invest in their health and well-being. It has been 45 days since Congress has failed to renew the Children’s Insurance Program, which insures about nine million American children. Nine million. That is nine million children whose parents will put off or avoid check ups that can catch diseases early. Nine million children whose life chances just got worse.

Our society does not love its children.

Our current U.S. Department of Education wants to cut funding to support after-school and summer programs. The current budget allocates $0 to Title II of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which purports to support high quality teaching and support for special education. Parents will have to choose between working or letting children be alone after school or on long summer days. Children need care and attention, and parents should not have to choose between earning a livable income and attending to those needs.

Our society does not love its children.

Politicians defend a pedophile’s pedophilia –– and even invoke religion to do so. Our society does not love its children.

Anybody who professionally cares for children is economically penalized. Their labor is not valued. Pediatricians make less than general practitioners. Educators, the stewards of the next generation, often work in inhospitable conditions and are asked to treat children as widgets, inputting knowledge so the children can output test scores, instead of as burgeoning people, with questions and needs and loves and worries.

Our society does not love its children. And it breaks my heart.